Hubble spots the farthest inbound comet so far

This frozen traveller shows the earliest signs of activity

C/2017 K2 PANSTARRS was discovered in May 2017 as part of NASA’s Near-Earth Object Observations Program.

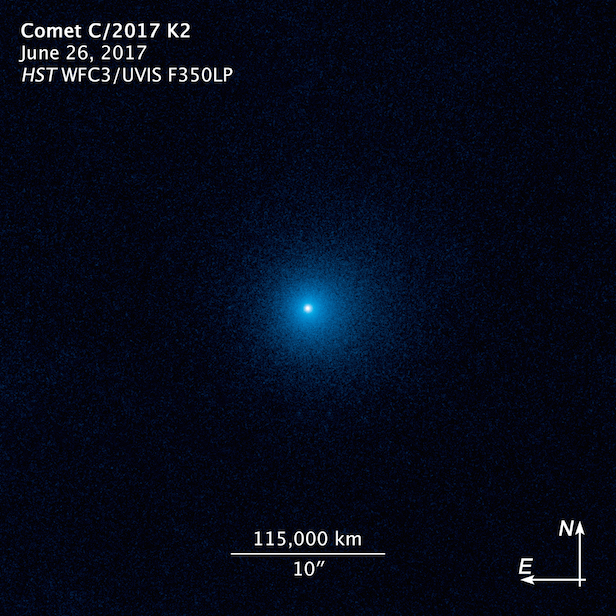

NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has imaged the farthest active inbound comet, which is currently 2.4 billion kilometres (1.5 billion miles) away. This is beyond the orbit of Saturn, and as the comet entered the Solar System’s planetary zone, Hubble observed – what is believed to be – the earliest signs of activity by a comet.

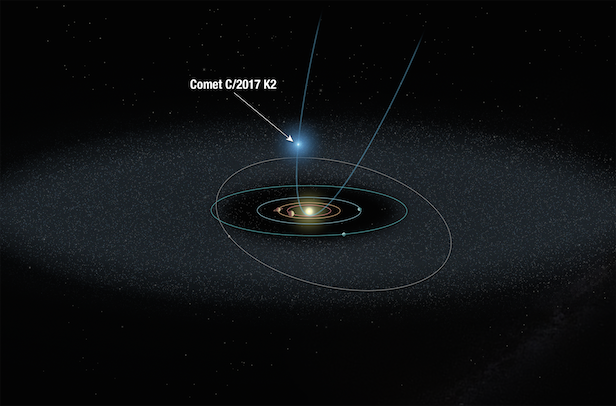

The comet, named C/2017 K2 (PANSTARRS) or just “K2”, originated from the Oort Cloud – the spherical cloud of comets surrounding our Solar System – and has been travelling for millions of years to reach this point. The Sun has kissed the nucleus of frozen gas and dust to create a 130,000-kilometre-wide (80,000-mile-wide) cloud of gaseous dust – also known as a coma – that envelops the comet’s heart.

“K2 is so far from the Sun and so cold, we know for sure that the activity — all the fuzzy stuff making it look like a comet — is not produced, as in other comets, by the evaporation of water ice,” says David Jewitt of the University of California, Los Angeles. “Instead, we think the activity is due to the sublimation [a solid changing directly into a gas] of super-volatiles as K2 makes its maiden entry into the solar system’s planetary zone. That’s why it’s special. This comet is so far away and so incredibly cold that water ice there is frozen like a rock.”

The Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System (PANSTARRS) in Hawai’i originally discovered K2 in May 2017, which was as part of NASA’s Near-Earth Object Observations Program. Jewitt then conducted follow up observation using Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3 in June 2017, observing K2 in more distinct detail.

C/2017 K2 PANSTARRS originated from the Oort Cloud, which is the freezing area comprised of billions of comets. Image creditL NASA/ESA/D. Jewitt (UCLA)

The Hubble observations of K2’s coma suggests that the sunlight is sublimating volatile elements on the nucleus, giving rise to the surrounding coma of oxygen, nitrogen, carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide. Not only that, but Hubble allowed Jewitt estimate the size of nucleus to be less than 19-kilometres (12-miles)-wide. “I think these volatiles are spread all through K2, and in the beginning billions of years ago, they were probably all through every comet presently in the Oort Cloud,” Jewitt explains. “But the volatiles on the surface are the ones that absorb the heat from the Sun, so, in a sense, the comet is shedding its outer skin. Most comets are discovered much closer to the Sun, near Jupiter’s orbit, so by the time we see them, these surface volatiles have already been baked off. That’s why I think K2 is the most primitive comet we’ve seen.”

Jewitt and his team will continue to study K2 as it continues with its approach towards the Sun in five years’ time, where it will be beyond Mars’ orbit. “We will be able to monitor for the first time the developing activity of a comet falling in from the Oort Cloud over an extraordinary range of distances,” Jewitt says. “It should become more and more active as it nears the Sun and presumably will form a tail.”

Keep up to date with the latest reviews in All About Space – available every month for just £4.99. Alternatively you can subscribe here for a fraction of the price!