A ring of cool, interstellar gas was detected around the Milky Way’s central black hole

By imaging this cool disk of gas rotate around the supermassive black hole, astronomers can watch how the accretion process unfolds

Artist impression of ring of cool, interstellar gas surrounding the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way. New ALMA observations reveal this structure for the first time. Image credit: NRAO/AUI/NSF; S. Dagnello

New Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) observations reveal a never-before-seen disk of cool, interstellar gas wrapped around the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way. This nebulous disk gives astronomers new insights into the workings of accretion: the siphoning of material onto the surface of a black hole. The results were recently published in the journal Nature.

Through decades of study, astronomers have developed a clearer picture of the chaotic and crowded neighbourhood surrounding the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way. Our galactic centre is approximately 26,000 light years from Earth and the supermassive black hole there, known as Sagittarius A* (A “star”), is four million times the mass of our Sun.

We now know that this region is brimming with roving stars, interstellar dust clouds, and a large reservoir of both phenomenally hot and comparatively colder gases. These gases are expected to orbit the black hole in a vast accretion disk that extends a few tenths of a light year from the black hole’s event horizon.

Until now, however, astronomers have been able to image only the tenuous, hot portion of this flow of accreting gas, which forms a roughly spherical flow and showed no obvious rotation. Its temperature is estimated to be a blistering 10 million degrees Celsius (18 million degrees Fahrenheit), or about two-thirds the temperature found at the core of our Sun. At this temperature, the gas glows fiercely in X-ray light, allowing it to be studied by space-based X-ray telescopes, down to scale of about a tenth of a light year from the black hole.

In addition to this hot, glowing gas, previous observations with millimetre-wavelength telescopes have detected a vast store of comparatively cooler hydrogen gas (about 10,000 degrees Celsius, or 18,000 degrees Fahrenheit) within a few light years of the black hole. The contribution of this cooler gas to the accretion flow onto the black hole was previously unknown.

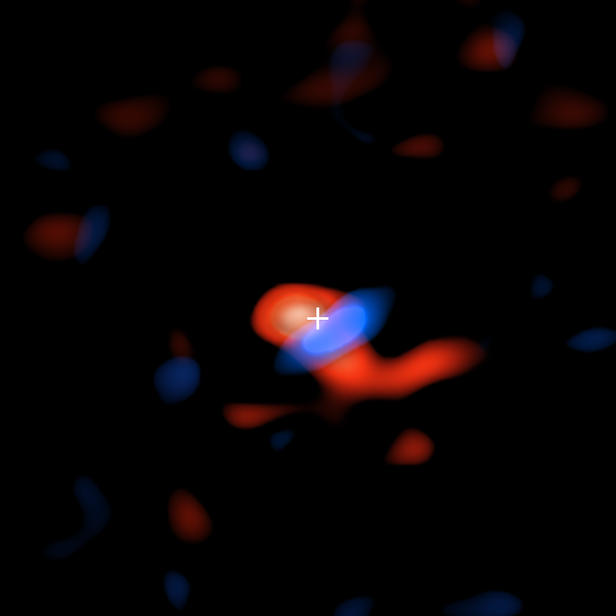

ALMA image of the disk of cool hydrogen gas flowing around the black hole at the centre of our galaxy. The colours represent the motion of the gas relative to Earth: the red portion is moving away, the blue represents gas moving toward Earth. Crosshairs indicate location of black hole. Image credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), E.M. Murchikova; NRAO/AUI/NSF, S. Dagnello

Although our galactic centre black hole is relatively quiet, the radiation around it is strong enough to cause hydrogen atoms to continually lose and recombine with their electrons. This recombination produces a distinctive millimetre-wavelength signal, which is capable of reaching Earth with very little losses along the way.

With its remarkable sensitivity and powerful ability to see fine details, ALMA was able to detect this faint radio signal and produce the first-ever image of the cooler gas disk at only about a hundredth of a light year away (or about 1,000 times the distance from the Earth to the Sun) from the supermassive black hole. These observations enabled the astronomers both to map the location and trace the motion of this gas. The researchers estimate that the amount of hydrogen in this cool disk is about one tenth the mass of Jupiter, or one ten-thousandth of the mass of the Sun.

By mapping the shifts in wavelengths of this radio light due to the Doppler effect (light from objects moving toward the Earth is slightly shifted to the “bluer” portion of the spectrum while light from objects moving away is slightly shifted to the “redder” portion), the astronomers could clearly see that the gas is rotating around the black hole. This information will provide new insights into the ways that black holes devour matter and the complex interplay between a black hole and its galactic neighbourhood.

“We were the first to image this elusive disk and study its rotation,” says Elena Murchikova, a member in astrophysics at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, United States, and lead author on the paper. “We are also probing accretion onto the black hole. This is important because this is our closest supermassive black hole. Even so, we still have no good understanding of how its accretion works. We hope these new ALMA observations will help the black hole give up some of its secrets.”

Keep up to date with the latest news in All About Space – available every month for just £4.99. Alternatively you can subscribe here for a fraction of the price!