Calibrating the cosmic mile markers

Astronomers need their measurements of type Ia supernovae to be precise in order to correctly measure the expansion of the universe

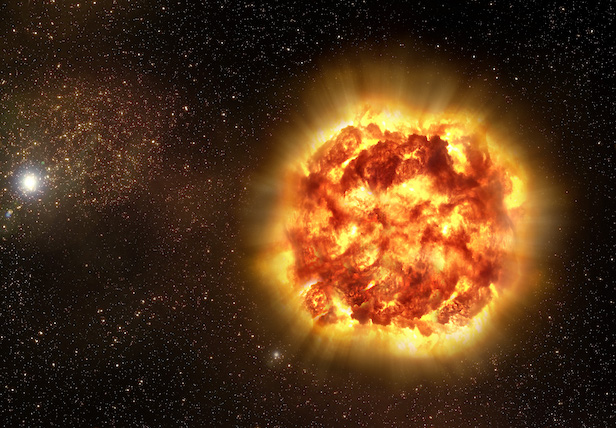

A type Ia supernovae occurs when a white dwarf star reaches a critical mass. Image credit: ESO

New work from the Carnegie Supernova Project provides the best-yet calibrations for using type Ia supernovae to measure cosmic distances, which has implications for our understanding of how fast the universe is expanding and the role dark energy may play in driving this process. Led by Carnegie astronomer Chris Burns, the team’s findings are published in The Astrophysical Journal.

Type Ia supernovae are fantastically bright stellar phenomena. They are violent explosions of a white dwarf—the crystalline remnant of a star that has exhausted its nuclear fuel—which is part of a binary system with another star.

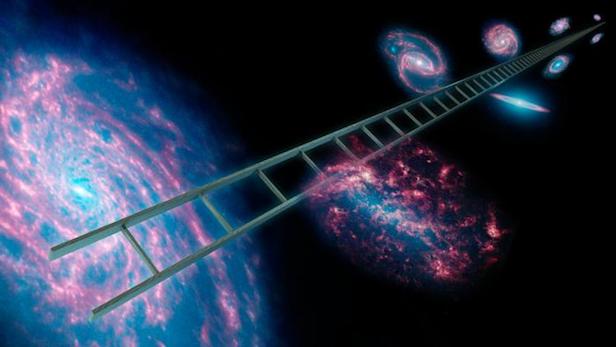

In addition to being exciting to observe in their own right, type Ia supernovae are also a vital tool that astronomers use as a kind of cosmic mile marker to infer the distances of celestial objects.

While the precise details of the explosion are still unknown, it is believed that they are triggered when the white dwarf approaches a critical mass, so the brightness of the phenomenon is predictable from the energy of the explosion. The difference between the predicted brightness and the brightness observed from Earth tells us the distance to the supernova.

Astronomers employ these precise distance measurements, along with the speed at which their host galaxies are receding, to determine the rate at which the universe is expanding. Thanks to the finite speed of light, not only can we measure how quickly the universe is expanding right now, but by looking farther and farther out into space, we see further back in time and can measure how fast the universe was expanding in the distant past. This led to the astonishing discovery in the late-1990s that the universe’s expansion is currently speeding up due to the repulsive effect of a mysterious “dark” energy. Improving the distance estimates made using type Ia supernovae will help astronomers better understand the role that dark energy plays in this cosmic expansion.

“Beginning with its namesake, Edwin Hubble, Carnegie astronomers have a long history of working on the Hubble constant, including vital contributions to our understanding of the universe’s expansion made by Alan Sandage and Wendy Freedman,” says Observatories Director John Mulchaey.

The ‘Cosmic Distance Ladder’ uses a series of astronomical objects, such as a type Ia supernova, to measure the distances to galaxies and beyond. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

However, the speed at which the brightness of type Ia supernova explosions fade away is not uniform. In 1993, Carnegie astronomer Mark Phillips showed that the explosions that take longer to fade away are intrinsically brighter than those that fade away quickly. This correlation, which is commonly referred to as the Phillips relation, allowed a group of astronomers in Chile, including Phillips and Texas A&M astronomer Nicholas Suntzeff, to develop type Ia supernovae into a precise tool for measuring the expansion of the universe.

Studying the supernovae using the near-infrared part of the spectrum was crucial to this finding. The light from these explosions must travel through cosmic dust to reach our telescopes, and these fine-grained interstellar particles obscure light on the blue end of the spectrum more than they do light from the red end of the spectrum in the same manner as smoke from a forest fire makes everything appear redder. This can trick astronomers into thinking that a supernova is farther away than it is. But working in the infrared allows astronomers to peer more clearly through this dusty veil.

“One of the Carnegie Supernova Project’s primary goals has been to provide a reliable, high-quality sample of supernovae and dependable methods for inferring their distances,” says lead author Burns.

“The quality of this data allows us to better correct our measurements to account for the dimming effect of cosmic dust” adds Mark Phillips, an astronomer at Carnegie’s Las Campanas Observatory in Chile and a co-author on the paper.

The calibration of these mile markers is crucially important, because there are disagreements between different methods for determining the universe’s expansion rate. The Hubble constant can independently be estimated using the glow of background radiation left over from the Big Bang. This cosmic microwave background radiation has been measured with exquisite detail by the Planck satellite, and it gives astronomers a more slowly expanding universe than when measured using type Ia supernovae.

“This discrepancy could herald new physics, but only if it’s real,” Burns explains. “So, we need our type Ia supernova measurements to be as accurate as possible, but also to identify and quantify all sources of error.”

Keep up to date with the latest news in All About Space – available every month for just £4.99. Alternatively you can make the most of our Christmas offer and subscribe here for a fraction of the price!