Planet formation caught in the act

Astronomers have not only directly imaged the newborn planet, but they have now proven that it is actively accreting mass

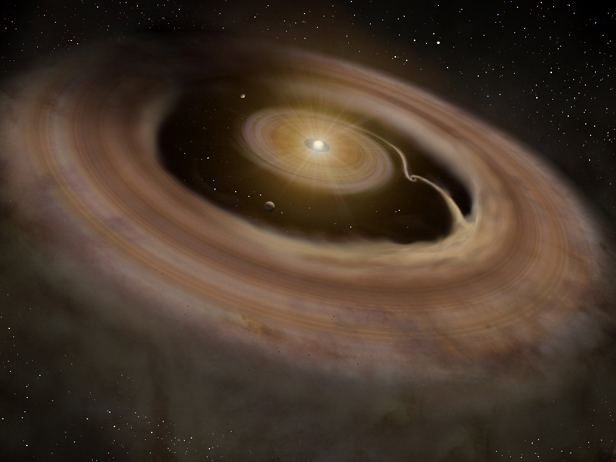

A new study of the young star PDS 70 suggests a planet may have cleared the gap in its surrounding disk as well. Image credit: The Graduate University for Advanced Studies/NAOJ

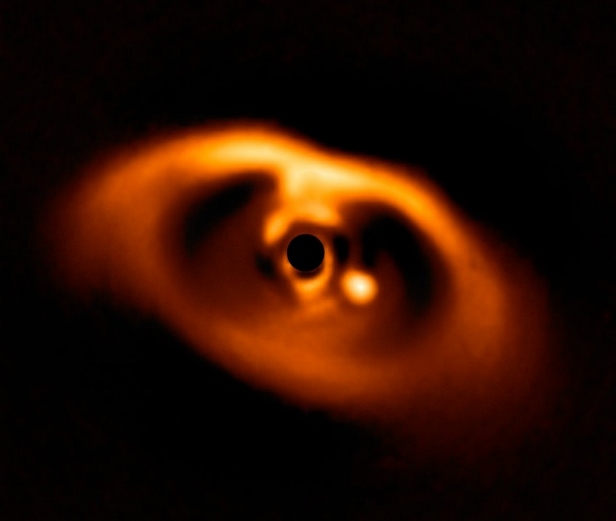

The gas giant PDS 70b made headlines in July 2018 as the first newly forming planet to ever be directly imaged. Now a team of scientists has gone a step further: they’ve captured evidence that this planet is actively accreting material, and they’ve measured the rate at which it’s growing.

In the recent era of high-resolution observations, indirect evidence of planet formation abounds. In particular, astronomers have captured a number of spectacular images of gapped disks surrounding young stars — disks in which astronomers think the first planets of those systems are being born. According to models, planets will grow as they accrete matter from the surrounding protostellar disk, simultaneously clearing a gap in the disk as they orbit.

In spite of the accumulation of indirect evidence, direct evidence was long lacking — until recently. The young (10 million years old) dwarf star PDS 70, located just 370 light-years from Earth, is surrounded by a disk with a distinctive gap. And in the month prior to the discovery, astronomers announced that they’ve directly imaged, and confirmed, the presence of a newborn planet orbiting within the gap.

But just demonstrating that a planet lies within the gap isn’t yet enough — the next step is to prove that this planet, PDS 70b, is actively accreting material. This is where high-contrast observations from the Magellan Adaptive Optics system come in.

The image of PDS 70 was taken in the infrared by ESO’s Very Large Telescope. This is the first clear image of a planet — PDS 70b, visible as the bright spot to the right of the masked-out star — caught in the act of forming. Image credit: (ESO/A. Müller et al.)

In a new study led by Kevin Wagner of the University of Arizona, Amherst College, and NASA NExSS Earths in Other Solar Systems Team, a team of scientists used the adaptive optics system on the 6.5-metre (21-foot) Magellan Clay Telescope in Chile to image the PDS 70 system in Hα (656 nm) and nearby continuum wavelengths. The presence of Hα emission at the location of the planet PDS 70b would indicate shocked, hot, infalling hydrogen gas — a smoking gun demonstrating that this planet is still accreting matter.

Sure enough, Wagner and collaborators detected the presence of an Hα signal from PDS 70b on two sequential nightsin the month of May 2018 — a signal that has less than a 0.1% probability of being a false positive. It seems fairly safe to say this baby planet is still growing.

But how fast is it growing, and how far along is it? Wagner and collaborators use their Hα luminosity measurements to calculate a mass accretion rate for PDS 70b, finding that the gas giant is growing at a rate of roughly 0.00000001 Jupiter masses per year. At this rate, and based on the age of the system, the astronomers estimate that PDS 70b likely accreted mass at a much higher rate in the past, and it has already acquired more than 90% of its final mass.

This nearby planet caught in the act of forming will make for an excellent study target in the future, as we continue to piece together our understanding of how planets are born and grow in protoplanetary disks.

Keep up to date with the latest news in All About Space – available every month for just £4.99. Alternatively you can subscribe here for a fraction of the price!