Unveiling the atmospheres of the TRAPPIST-1 system

Three Earth-sized exoplanets orbiting TRAPPIST-1 lack hydrogen in their atmospheres, which could be a good sign for its habitability

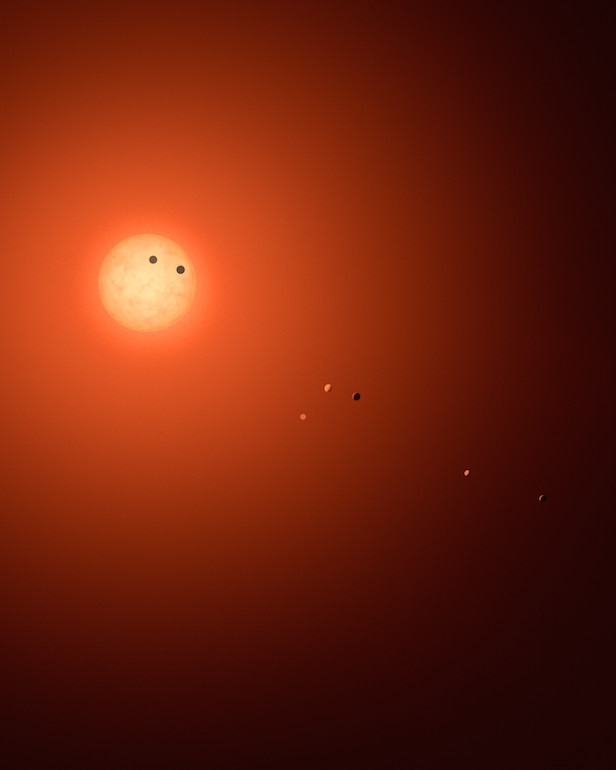

The seven exoplanets are orbiting closer to TRAPPIST-1 than Mercury is to the Sun. Image credit: NASA

Only days after the news that researchers singled out two of the seven exoplanets orbiting the TRAPPIST-1 star to be likely habitable (d and e), it has been announced that NASA and ESA’s Hubble Space Telescope has conducted the first spectroscopic analysis of the atmospheres on four of the planets, d, e, f and g. Out of these four exoplanets, astronomers can rule out the presence of puffy, hydrogen-rich atmospheres, such as Neptune, on d, e and f. This could be a sign that these three Earth-sized planets, only 40 light years away, have shallow atmospheres that are rich in heavier elements, much like Earth’s.

Since the initial TRAPPIST-1 announcement in May 2016, the prospect of seven Earth-sized rocky planets orbiting an ultra-cool red dwarf star 40 light years away has gained much public attention. Especially as three of these planets (e, f and g) lie within the star’s habitable zone, which is the region around the star where water theoretically exists as a liquid. These three planets with extra one, d, e, f and g, have recently been subjects of spectroscopic analysis by Hubble.

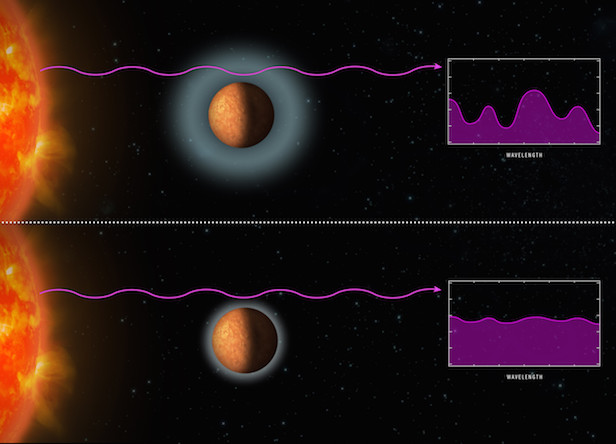

As each planet only takes a matter of days to orbit TRAPPIST-1 once, Hubble was able to use its infrared-sensitive Wide Field Camera 3 to scout for the elemental signature of hydrogen. When the planet is positioned between the host star and us, the starlight passes through the planet’s atmosphere and carries its composition fingerprint to us on Earth in order to study. “The planets are close enough to their host star, and they have very short orbital periods, which means there are lots of opportunities to make observations,” says Nikole Lewis of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Maryland.

Starlight passing through the atmosphere of an exoplanet can reveal its composition, including the presence of hydrogen. Image credit: NASA/ESA/Z. Levy (STScl)

Hydrogen is a known potent greenhouse gas that normally encompasses planets orbiting closer to its host star. If the Hubble results showed that hydrogen is present in the planets’ atmospheres, this would mean the planets would have much greater heat retention than Earth’s atmosphere. The surface would be scorching, and it would make it impossible for life, as we know it, to survive in this sort of environment. Thankfully, Hubble did not detect a hydrogen-rich atmosphere, making it more likely to be hospitable for TRAPPIST-1d, e and f. The results for TRAPPIST-1g’s atmosphere remained inconclusive, and require further observation in order to rule the presence of hydrogen.

“Hubble is doing the preliminary reconnaissance work so that astronomers using Webb know where to start,” says Lewis. “Eliminating one possible scenario for the makeup of these atmospheres allows the Webb telescope astronomers to plan their observation programs to look for other possible scenarios for the composition of these atmospheres.”

By not detecting large amounts of hydrogen in the planets’ atmospheres, it has broke ground for future observations using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). When it is launched in 2019, JWST will use its incredible infrared capabilities to probe even further into the planets’ atmospheres, including the detection of heavier elements such as carbon monoxide, methane, water and oxygen. These heavier elements will either make of break the theory that these planets could be habitable and the prime place to look at for alien life.

Keep up to date with the latest reviews in All About Space – available every month for just £4.99. Alternatively you can subscribe here for a fraction of the price!