Jupiter’s aurorae have a deeper influence on the gas giant than originally thought

Aurora on Jupiter can reach two to three times deeper into its atmosphere than the aurora experienced on Earth

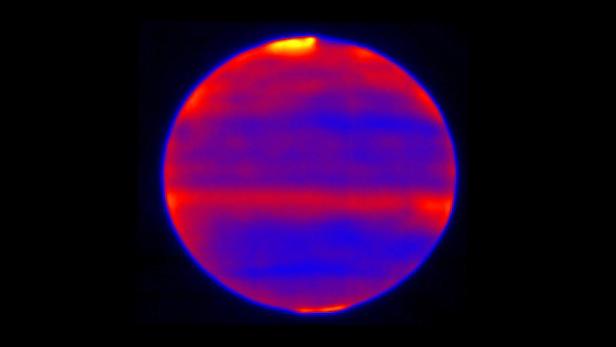

Scientists used red, blue and yellow to infuse this infrared image of Jupiter’s atmosphere (red and yellow indicate the hotter regions). Image credit: NAOJ and NASA/JPL-Caltech

New Earth-based telescope observations show that aurorae at Jupiter’s poles are heating the planet’s atmosphere to a greater depth than previously thought – and that it is a rapid response to the solar wind.

“The solar wind impact at Jupiter is an extreme example of space weather,” says James Sinclair of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, United States, who led new research published 8 April 2019 in Nature Astronomy. “We’re seeing the solar wind having an effect deeper than is normally seen.”

Aurorae at Earth’s poles (known as the aurora borealis at the North Pole and aurora australis at the South Pole) occur when the energetic particles blown out from the Sun (the solar wind) interact with and heat up the gases in the upper atmosphere. The same thing happens at Jupiter, but the new observations show the heating goes two or three times deeper down into its atmosphere than on Earth, into the lower level of Jupiter’s upper atmosphere, or stratosphere.

Understanding how the Sun’s constant outpouring of solar wind interacts with planetary environments is key to better understanding the very nature of how planets and their atmospheres evolve.

Sensitive to Jupiter’s stratospheric temperatures, the areas that are more yellow and red indicate the hotter regions. Image credit: NAOJ and NASA/JPL-Caltech

“What is startling about the results is that we were able to associate for the first time the variations in solar wind and the response in the stratosphere – and that the response to these variations is so quick for such a large area,” says JPL’s Glenn Orton, co-author and part of the observing team.

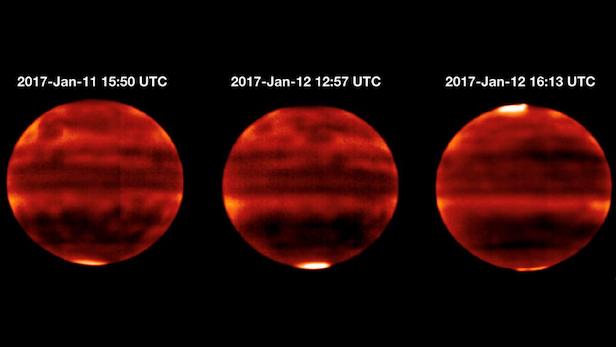

Within a day of the solar wind hitting Jupiter, the chemistry in its atmosphere changed and its temperature rose, the team found. An infrared image captured during their observing campaign in January, February and May of 2017 clearly shows hot spots near the poles, where Jupiter’s aurorae are. The scientists based their findings on observations by the Subaru Telescope, atop the summit of Mauna Kea in Hawaii, which is operated by the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan.

The telescope’s Cooled Mid-Infrared Camera and Spectrograph (COMICS) recorded thermal images – which capture areas of higher or lower temperatures – of Jupiter’s stratosphere.

“Such heating and chemical reactions may tell us something about other planets with harsh environments, and even early Earth,” says Yasumasa Kasaba of Tohoku University, who also worked on the observing team.

Keep up to date with the latest news in All About Space – available every month for just £4.99. Alternatively you can subscribe here for a fraction of the price!