Reflecting on the Rosetta mission

On the second anniversary of Rosetta’s conclusion, astronomers look back on what was learnt and what’s still to come

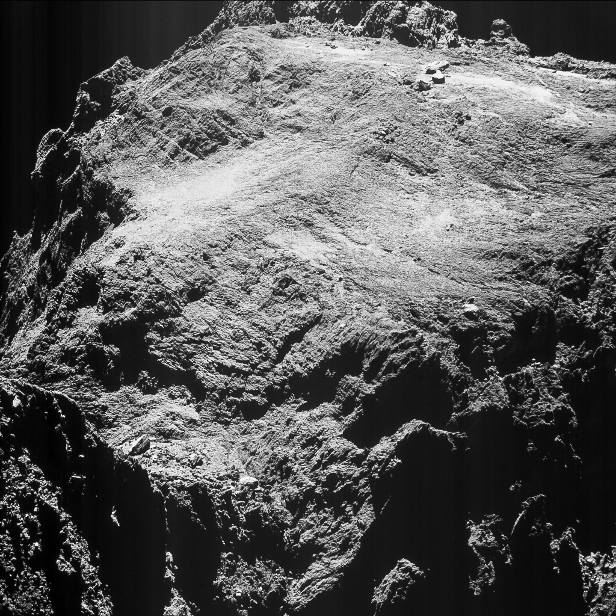

The ESA’s Rosetta probe flew over the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko at a distance of mere kilometres, which enabled the measurement of noble gases argon, krypton and xenon. Image credit: ESA/NAVCAM

On 30 September 2016, the active phase of the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Rosetta mission came to an end with the controlled crash landing of the probe on the surface of the comet Chury. Due to the key experiment of the University of Bern in Switzerland, ROSINA, more information regarding the origin of our solar system was acquired. However, over two million data records are still awaiting evaluation.

For more than two years, the ESA’s Rosetta mission investigated the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko—”Chury” for short—in great detail, even placing the Philae landing module on its surface during the process. What’s more, it was under the leadership of the University of Bern that the ROSINA (the Rosetta Orbiter Spectrometer for Ion and Neutral Analysis) mass spectrometer was developed, built, tested and operated on the comet via telecommand. ROSINA determined many components of Chury’s atmosphere, many of which for the first time on a comet. “The air on the comet would probably be pungent”, was the phrase used by Kathrin Altwegg, ROSINA mass spectrometer project leader, to humorously describe the composition of Chury’s atmosphere.

The Rosetta mission was aimed at collecting more information on the origin of our solar system. For example, one of the big questions is how water came to exist on Earth as, in its earliest days, our planet was extremely hot and probably covered with an ocean of lava. Is it possible that comet impacts were responsible for bringing water to Earth at a later date? “Probably not from comets like Chury”, says Kathrin Altwegg. By means of isotopic analysis, a sort of DNA for chemical elements, Altwegg and her team were able to demonstrate that the water on the comet Chury was different from water found on Earth. There are also indications that the ice on the comet is older than our solar system, meaning that this water had already formed in the cold molecular cloud from which our solar system then took shape.

One surprise was the evidence found for molecular oxygen on Chury as, on Earth, this is often associated with life. “But there is no life on the comet”, says Kathrin Altwegg. What’s more, molecular oxygen is very reactive, yet was nevertheless able to withstand billions of years in the comet’s ice. “Entire research teams are currently occupied with how this molecular oxygen came into being, and how it is frozen in the comet’s ice”, explains PD Dr. Martin Rubin, co-investigator in the ROSINA team.

Due to the relative abundance of highly-volatile gases, the researchers were also able to determine the temperature at which the comet was formed. “Chury was formed at around minus 250 degrees Celsius (minus 418 degrees Fahrenheit), i.e. in the bitter cold” says Martin Rubin, main author of the study at the time.

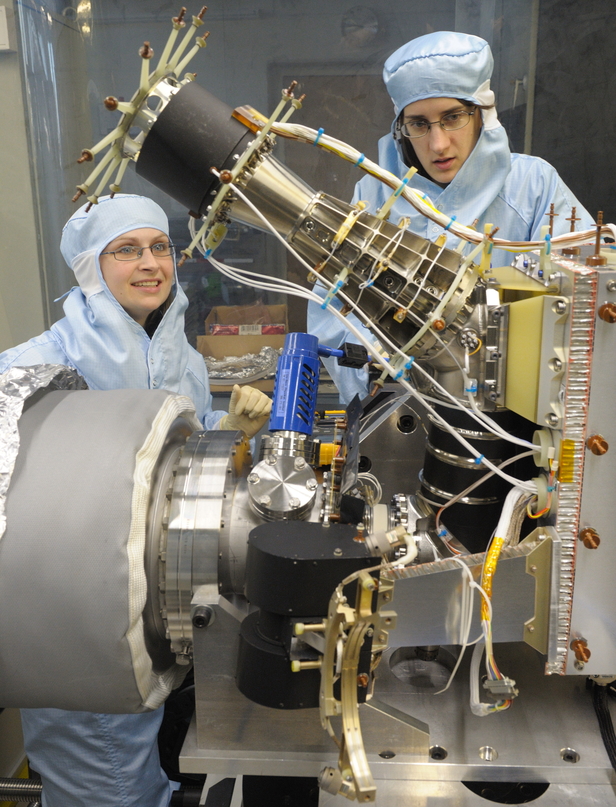

Two PhD students carry out tests with the ROSINA-DFMS mass spectrometer. In doing so, they have an exact copy of the instrument at their disposal as was on board the Rosetta probe. Image credit: University of Bern/Thomas Wüthrich

What’s more, thanks to isotopic analysis, the researchers were able to demonstrate that, if not water, at least a considerable part of the Earth’s atmosphere may have originated from comets. Of particular interest was further the existence of many simple organic compounds, even including the amino acid glycine, which ROSINA was able to detect. “The amount of organic compounds on Chury is considerable, which opens up the possibility that comet impacts may have facilitated the emergence of life on Earth.” says Kathrin Altwegg.

The end of the Rosetta mission and, with it, the end of ROSINA’s measurements, by no means meant the end of research work. “We have over two million data records,” emphasises Kathrin Altwegg, “and many of them have not been evaluated yet”. This work should continue to keep the researchers busy for years. “Our chief goal is the analysis of the data; after all, that’s why we flew to Chury in the first place” says Martin Rubin.

The ESA is financed by its member states, including Switzerland. Accordingly, this data also belongs to the general public. “The raw data as it was measured by ROSINA and sent back to Earth is already available to the public” says Martin Rubin. Currently, the team is working on further preparing this data so that it is easier to analyse and so that it can also be used to some extent by researchers who do not have a background in mass spectrometry. The data will be available on the ESA server in a few months’ time and will be able to be downloaded without having to register.

Against this backdrop, Kathrin Altwegg would particularly like to thank the sponsors, the

State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation SERI, the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) and the canton of Bern for their support over the years: “Rosetta/ROSINA would never have achieved the success it did without this strong support”.

Keep up to date with the latest news in All About Space – available every month for just £4.99. Alternatively you can subscribe here for a fraction of the price!