Space junk menace: New guidelines urged to help fight orbital debris threat

Spacecraft designers and operators need to be proactive, a new organisation argues

Illustration of a space debris field, as depicted in the film “Space Junk 3D.” Image credit: Space Junk 3D, LLC

The final frontier may need a little taming.

About 2,000 operational satellites currently zoom around Earth, studying our planet’s weather, beaming down telecommunications data and performing a variety of other tasks. But that number has been rising steadily as the costs of building and launching spacecraft fall, and it’s about to make some big leaps.

For example, SpaceX, Amazon and OneWeb all plan to set up internet-satellite megaconstellations in the near future. This past May, SpaceX launched to low-Earth orbit the first 60 members of its Starlink network, which could eventually feature up to 12,000 satellites.

But not all of the coming Earth-circling spacecraft will be operated by aerospace professionals working for deep-pocketed companies or government agencies. A fair number will be run by neophytes who just a few short years ago couldn’t have dreamed of being part of the space scene.

Indeed, that’s already happening, because “even, frankly, elementary schools can afford to put up these little experimental satellites,” Walter Scott, chief technology officer of Maxar Technologies, told Space.com.

This opening of space is very much a good thing, but it does come with some risks, Scott and others have noted. As Earth orbit gets more crowded, the chance of a collision between satellites goes up — especially if some of those satellites are bare-bones craft being controlled by people without much experience.

And satellite smashups can be a very big deal. In February 2009, for example, the United States’ active Iridium 33 communications satellite slammed into a dead Russian craft called Cosmos 2251. The collision had created 1,800 new pieces of tracked debris by the following October, about 10 percent of the monitored population of orbital debris at the time. (The vast majority of space junk is too small to be tracked, however; millions of tiny flecks zoom around Earth unseen by our instruments.)

Each piece of orbital debris is a bullet whizzing through space at thousands of miles per hour, posing a potential threat to other spacecraft. So one collision could theoretically lead to another, which leads to another, and so on in a catastrophic cascade known as the Kessler syndrome. In the worst-case scenario, such crashes could render large swaths of space unusable for the foreseeable future.

But we can stave off the Kessler syndrome — or at least minimise the odds that it happens anytime soon — if spacecraft builders and operators follow a few simple rules, according to the Space Safety Coalition (SSC).

The SSC, a newly established group of space-industry stakeholders, laid out those proposed voluntary guidelines last month in a document called “Best Practices for the Sustainability of Space Operations.”

There are space-junk mitigation guidelines on the books already, which were drawn up by the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee and the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space. But those guidelines were last revised in 2007, the SSC noted.

“Plans to increase our space population with more cubesats and other small satellites, as well as new, large constellations of satellites, were not envisioned when the above-mentioned guidelines and standards were established,” the new “best practices” document states. “These new planned spacecraft and constellations, coupled with improvements in space situational awareness, space operations and spacecraft design, all provide an opportunity to expand upon established space operations and orbital debris mitigation guidelines and best practices.”

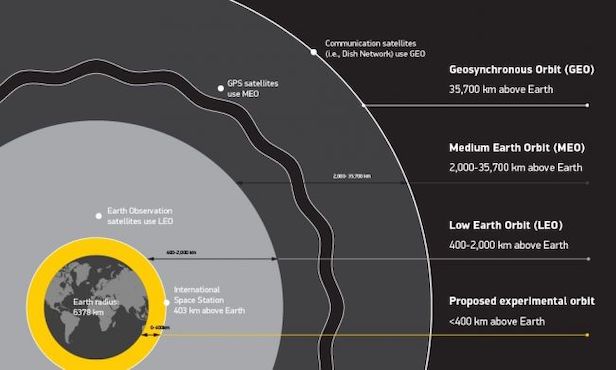

One of the key new recommendations is that all spacecraft that operate at an altitude above 400 kilometres (250 miles) should feature a propulsion system that allows them to manoeuvre their way out of potential collisions.

That’s a natural dividing line, Scott said; the International Space Station circles at about that altitude, and nobody wants out-of-control satellites falling back to Earth through the orbiting lab’s path. Also, below 400 kilometres, there’s enough atmosphere to create significant drag on spacecraft, causing them to de-orbit relatively quickly when their operational lives are over.

(The space community could designate the below-400-kilometres region an “experimental zone,” Scott wrote in a recent blog post. Such a move would keep space “affordable for operators of the growing number of inexpensive, experimental or educational cubesats,” he wrote.)

The zone below an altitude of 400 kilometres (250 miles) could be designated an experimental region, to keep space accessible and affordable for a variety of people. Image credit: Maxar Technologies

The SSC also recommends that satellite designers consider building encryption into their command and control systems, so that spacecraft cannot be hijacked by hackers intent on causing havoc in orbit. And the best practices include anti-littering guidelines. For example, the handlers of satellites that operate in low-Earth orbit should include in their launch contracts a requirement that rocket upper stages be disposed of promptly, via a controlled reentry into Earth’s atmosphere.

As of 15 October 2019, 31 space-industry stakeholders have endorsed the new guidelines. And there are some big names in that group, including Maxar (the parent company of satellite operator DigitalGlobe and the spacecraft manufacturer SSL, among other subsidiaries), OneWeb, Rocket Lab, Iridium, SES and Intelsat.

“You don’t want to wait for a disaster before you take action,” Scott said. “It really is time, and you’re seeing operators like Maxar and OneWeb being proactive.”

Space fans and satellite operators had two occasions to contemplate such a disaster just last month. On 2 September 2019, the European Space Agency moved its Aeolus Earth-observation satellite after learning there was a 1-in-1,000 chance it would hit one of SpaceX’s Starlink craft.

And there was a 5.6 percent probability that Bigelow Aerospace’s Genesis II experimental habitat and Russia’s Cosmos 1300 satellite would smash into each other on 18 September. The two big craft ended up sailing safely past each other, but not because evasive manoeuvres were taken. Both vehicles are defunct, part of the ever-growing population of orbital debris.

Keep up to date with the latest news in All About Space – available every month for just £4.99. Alternatively you can subscribe here for a fraction of the price!